Scots Pine Bonsai: The European Classic That Changed My Perspective on Pine Bonsai

My First Encounter with Pinus sylvestris

For a long time, I thought Japanese Black Pine was the only proper bonsai pine. I assumed people who were serious about bonsai would only grow Pinus thunbergii, maybe White Pine at most. Scots Pine did not seem like a bonsai tree to me, only a wild tree from the Scottish Highlands.

Then I visited a bonsai exhibition in Amsterdam in 2018. There, sitting on a plain wooden stand, was a Scots Pine that stopped me in my tracks. The orange-red bark glowed under the gallery lights. The needles were a vibrant blue-green, forming tight, compact candles. The trunk had movement and character that made it look ancient, even though the owner told me it was only 35 years old.

I bought my first Scots Pine seedling the next week. Seven years later, it’s become one of my favorite trees to work with—and I’m going to tell you why this underappreciated species deserves more attention in the bonsai world.

What is a Scots Pine Bonsai?

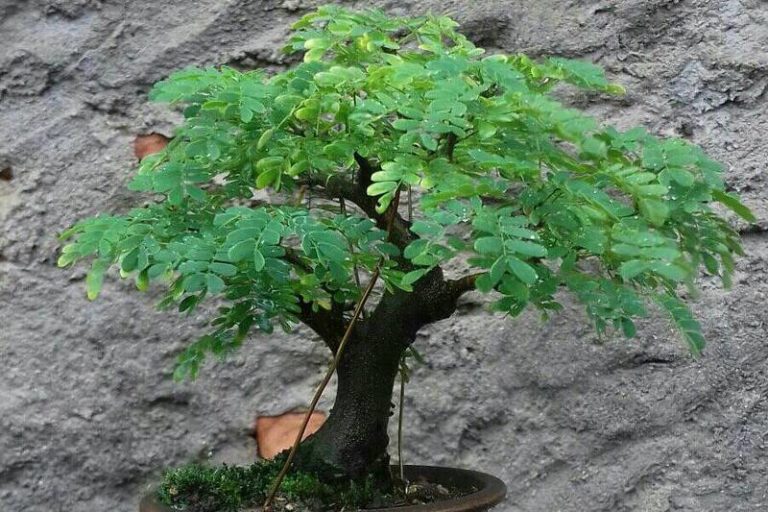

Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris) is a two-needle pine native to Europe and parts of Asia. It’s one of the most widely distributed pine species in the world, ranging from Scotland to Siberia. In bonsai form, these trees are cultivated and trained to replicate the windswept, weathered pines you’d find clinging to rocky hillsides in the Scottish Highlands or Scandinavian mountains.

Unlike their Japanese cousins, Scots Pines have a distinctive reddish-orange bark that becomes more pronounced with age, blue-green needles that are shorter and more manageable than many pine species, and a naturally irregular growth pattern that lends itself beautifully to literati and informal upright styles.

History and Cultural Significance

While pine bonsai cultivation is most famously associated with Japan, European bonsai artists have been working with Scots Pine since at least the 1970s. The species gained serious recognition in the 1990s when European bonsai masters like Walter Pall began showcasing what could be achieved with native European material.

In traditional Scottish and Nordic cultures, Scots Pines are symbols of resilience and longevity—these trees can live 300+ years in the wild, often in harsh, nutrient-poor conditions. That same toughness makes them surprisingly forgiving as bonsai material, despite their reputation as “advanced” trees.

I learned this firsthand when I accidentally left my young Scots Pine in full sun during a heat wave without adequate watering. Any other pine would have turned brown and possibly died. My Scots Pine? It sulked for a few weeks, then bounced back completely. They’re tougher than people think.

What Makes Scots Pine Special for Bonsai

After working with this species for seven years, here’s what I’ve come to appreciate:

The Bark is Incredible

That orange-red bark isn’t just pretty—it develops relatively quickly compared to other pines. My 15-year-old tree already shows good bark color and texture. On Japanese Black Pine, you’d be waiting 30+ years for similar development.

The bark tends to flake in irregular plates, creating visual interest even on younger trees. As the tree ages, the upper trunk and branches develop this glowing copper color while the lower trunk becomes deeply fissured and gray-brown. The contrast is stunning.

Needles That Actually Work at Bonsai Scale

Scots Pine needles are typically 1.5-3 inches long—significantly shorter than many pine species. After proper candling and development, you can get them down to 0.5-1 inch, which looks proportional even on smaller bonsai.

The blue-green color is also distinctive. It’s not the dark, somber green of Black Pine or the bright green of White Pine. It’s this silvery blue-green that catches light beautifully and provides excellent contrast against the warm bark tones.

They Respond Well to Styling

Scots Pines naturally grow with irregular, somewhat chaotic branching. In the wild, this looks windswept and characterful. In bonsai, it means you’re working with the tree’s natural tendencies rather than fighting them.

They also tolerate aggressive techniques better than you’d expect. I’ve done root work that would have killed more sensitive pines, and my Scots Pines just kept growing. They back-bud reasonably well for a pine (though not as readily as Black Pine), and they tolerate wiring at almost any time of year.

Types and Varieties of Scots Pine for Bonsai

Scots Pine has numerous naturally occurring varieties across its range. Here are the ones I’ve personally worked with or seen used successfully in bonsai:

Pinus sylvestris var. sylvestris (Typical Form)

This is your standard Scots Pine—the one you’ll find in most nurseries. It works perfectly well for bonsai. The needles are medium length (2-3 inches), and the bark develops that classic orange-red color by age 10-15.

Best for: General bonsai use, all sizes and styles

Pinus sylvestris ‘Watereri’ (Dwarf Form)

This dwarf cultivar naturally grows more compactly with shorter needles. I have one that I started from nursery stock five years ago, and it’s been excellent. The compact growth means less aggressive pruning to maintain proportions.

Best for: Shohin and smaller bonsai (under 12 inches)

Pinus sylvestris ‘Beuvronensis’

Another dwarf form with even tighter growth than ‘Watereri.’ The needles are shorter and denser. I’ve seen gorgeous shohin made from this cultivar, though it can be harder to find in nurseries.

Best for: Shohin bonsai, rock plantings

Scottish Highland Forms

If you can source material collected from the Scottish Highlands (legally and ethically, of course), these trees often have naturally twisted trunks, compact growth, and exceptional character. A friend in Edinburgh works exclusively with Highland-collected material, and the trees are spectacular.

Best for: Literati, windswept, and informal upright styles

How to Grow a Scots Pine Bonsai

Let me walk you through the actual process—not the theory, but what’s worked for me over seven years.

Starting Material: Three Options

Option 1: Nursery Stock (My Recommendation for Beginners)

I’ve started four Scots Pines from nursery stock. It’s affordable, readily available, and you can develop a decent bonsai in 5-7 years. Look for:

- Trees with interesting trunk movement (avoid straight, telephone-pole trunks)

- Low first branch (ideally within 1/3 of the trunk height)

- Good nebari potential (roots spreading in multiple directions)

- Healthy, vibrant foliage

Garden centers often sell Scots Pine as landscape trees. In spring, you can find 3-5 year old trees for $20-40. That’s where three of mine came from.

Option 2: Seedlings (For the Patient)

Growing from seed takes forever—figure 10+ years before you have something resembling a bonsai. But if you enjoy the entire journey and want maximum control, this is an option. I started some seedlings four years ago mostly as an experiment. They’re still pencil-thick.

Option 3: Collected Material (Advanced)

Collecting Scots Pine from the wild (where legal) can yield incredible material. The trees growing in harsh conditions develop character naturally—thick trunks with minimal height, windswept forms, and that weathered look. However, collection success rates are maybe 50-60% in my experience, and only attempt this if you have proper permissions and knowledge.

Soil Mix That Actually Works

I killed my first Scots Pine with heavy soil. Lesson learned.

My current mix for established trees:

- 50% akadama

- 30% pumice

- 20% lava rock

For younger trees or newly collected material, I add 10-15% pine bark for organic content.

The key is drainage. Scots Pines tolerate dry conditions better than wet feet. In doubt, err on the side of better drainage.

Location and Climate

Here’s where Scots Pine excels: it’s cold-hardy. In my zone 7a garden, these trees stay outside year-round, even when temperatures drop to 5-10°F (-15 to -12°C). In fact, they need winter dormancy—trying to grow them indoors is a recipe for disaster.

Place your Scots Pine where it gets:

- Full sun: Minimum 6 hours, but more is better

- Good air circulation: Prevents fungal issues

- Protection from harsh afternoon sun in summer: The blue-green needles can bleach in intense heat

I keep mine on benches from spring through fall, then move them to the ground in winter for added root protection during extreme cold snaps.

Watering Reality

This is where Scots Pine is more forgiving than other species. They tolerate brief dry periods without immediately browning out. That said, proper watering is still critical.

My approach:

- Water thoroughly when the soil surface feels dry but still has moisture 1 inch down

- In summer: Usually daily, sometimes twice daily during heat waves

- In spring/fall: Every 2-3 days

- In winter: Weekly, or whenever the soil isn’t frozen

I killed a young tree by overwatering in winter. The roots rotted because the soil stayed cold and wet for weeks. Now I barely water in winter—just enough to prevent complete desiccation.

Fertilizing Strategy

Scots Pines aren’t heavy feeders, but they need consistent nutrition during the growing season.

My fertilizing schedule:

- Spring (March-May): Balanced organic fertilizer (I use Biogold), applied monthly

- Summer (June-August): Continue balanced fertilizer

- Fall (September-October): Switch to low-nitrogen fertilizer to harden off growth before winter

- Winter: No fertilizer

I use organic pellets because they release slowly and I can’t burn the tree by over-applying. Chemical fertilizers work too, but you need to be more careful with dosage.

Pruning and Development

Here’s where Scots Pine differs significantly from Japanese Black Pine. The techniques aren’t identical, and learning that cost me some branches.

Candle Pruning:

Scots Pines produce candles (new growth shoots) in spring. On vigorous trees, these can extend 4-6 inches. To control needle length and promote back-budding:

- Wait until candles fully extend and needles just start emerging (usually late May/early June for me)

- Cut or pinch back strong candles by 2/3

- Cut weaker candles by 1/2 or leave them alone

- This encourages shorter needles and a second flush of growth

I was too aggressive my first year and cut candles too early. The tree responded with weak, thin candles the next year. Timing matters.

Needle Plucking:

In fall (September/October), I remove old needles to let light into the interior branches:

- Keep current year’s needles

- Remove 50-75% of the previous year’s needles

- Remove all needles older than 2 years

This seems drastic, but it works. The tree looks sparse for a few weeks, then fills in beautifully the following spring.

Wiring and Styling

Scots Pine branches are flexible when young but become brittle with age. I’ve snapped more than one branch by getting too aggressive with thick wood.

My wiring approach:

- Wire new growth in summer after it hardens (July-August)

- Use aluminum wire—it’s gentler than copper

- Wire branches in sections rather than trying to bend everything at once

- Check wire every 2-3 months for bite marks; Scots Pine bark scars easily

For thick branches that won’t bend, I use guy wires instead of trying to force them. It’s slower but safer.

Preferred styles:

- Literati: Scots Pine naturally looks good in this style

- Informal Upright: Works with the irregular branching

- Windswept: Matches the natural habitat aesthetic

- Cascade/Semi-Cascade: Can work but requires more training

I’ve tried formal upright with Scots Pine. It looks forced and unnatural. Work with the tree’s character, not against it.

Repotting

Scots Pines have strong root systems that can become pot-bound quickly in the first years of development.

My repotting schedule:

- Young trees (under 10 years): Every 2 years

- Mature trees: Every 3-4 years

- Old trees: Every 5+ years

Best timing is early spring (March) just before buds swell. I’ve also successfully repotted in fall, but spring is safer.

During repotting, I remove about 1/3 of the root mass and untangle circling roots. Scots Pines tolerate root work better than most pines, but don’t get overconfident. I killed a tree by removing 50% of the roots in one session.

Benefits of Growing Scots Pine Bonsai

After seven years with this species, here’s what I genuinely appreciate:

Cold Hardy and Low-Maintenance

Once established, these trees basically take care of themselves. They don’t need winter protection (in most climates), they tolerate occasional watering lapses, and they’re resistant to most pests and diseases. For someone with 20+ bonsai trees, that reliability matters.

Unique Aesthetic

When you show up to a bonsai exhibition with a Scots Pine, you stand out. Everyone has Japanese Black Pines and Junipers. Scots Pine offers something different—that distinctive bark, the blue-green foliage, the windswept character.

Faster Development Than Japanese Pines

My Scots Pines develop good trunk thickness and bark character faster than comparable Japanese Black Pines. If you’re impatient (like me), that’s a real advantage.

European Connection

For bonsai practitioners in Europe or those with European heritage, there’s something satisfying about working with a native European species. You’re connecting to your local environment and traditions rather than only copying Japanese aesthetics.

Teaching Tool

Scots Pine is forgiving enough for adventurous beginners but sophisticated enough to challenge advanced practitioners. I’ve used my trees to teach candling, wiring, and styling techniques because mistakes aren’t as catastrophic as with more sensitive species.

Styling and Design Considerations

The best Scots Pine bonsai I’ve seen share certain design elements:

Embrace the Irregularity

Trying to create perfect, symmetrical branch pads on Scots Pine looks wrong. The species naturally grows with irregular, somewhat chaotic branching. Work with that. Create asymmetry. Let some branches be thicker or longer than “proper” bonsai proportions suggest.

My best tree has a thick lower branch that technically violates every rule about branch placement. But it looks right because it matches how Scots Pines grow in nature.

Show the Bark

That orange-red bark is your tree’s best feature. Design with that in mind:

- Remove lower branches to reveal trunk character

- Consider stripping some bark sections to create deadwood (jin/shari) that contrasts with the living bark

- Position the tree so light catches the bark

Consider Natural Habitat

In the wild, Scots Pines often grow in exposed, harsh conditions. They’re windswept, irregular, and tough-looking. Channel that aesthetic:

- Literati styles work beautifully

- Windswept forms echo their natural habitat

- Avoid overly refined, manicured appearances

Pot Selection

I’ve learned this through trial and error: Scots Pines look best in unglazed, earth-toned pots. The warm bark color clashes with bright glazes.

Colors that work:

- Warm browns and tans

- Gray-brown

- Unglazed buff

- Subtle reddish-browns

I made the mistake of putting one in a bright blue pot. It looked terrible—too much visual competition.

Care and Maintenance Through the Seasons

Spring (March-May)

This is the busy season for Scots Pine. New candles emerge, and the tree puts on most of its annual growth.

Tasks:

- Repot if scheduled

- Begin fertilizing

- Monitor candle development

- Plan your candling strategy

- Check wire from last year

Summer (June-August)

Candle pruning happens in early summer, then the tree enters a growth pause during the hottest months.

Tasks:

- Execute candle pruning (early June)

- Wire new growth after it hardens (July-August)

- Water frequently—sometimes twice daily in heat

- Watch for spider mites (rare but possible)

Fall (September-November)

This is needle-plucking season and the time to prepare the tree for winter.

Tasks:

- Needle plucking (September/October)

- Final fertilization with low-nitrogen fertilizer

- Remove wire if biting into bark

- Check for branch die-back and prune as needed

- Prepare for dormancy

Winter (December-February)

The tree is dormant. There’s not much to do, which is nice after a busy year.

Tasks:

- Minimal watering

- Protect from extreme temperature swings (though Scots Pine is very hardy)

- Check for winter damage (rare)

- Plan next year’s styling work

- Clean up around the pot

Common Problems and Solutions

Problem: Needles Turning Yellow/Brown

Causes: Overwatering, underwatering, or nutrient deficiency

Solution: Check soil moisture. If soggy, reduce watering and check drainage. If bone dry, water more consistently. If watering seems fine, increase fertilization.

I had yellowing needles on one tree despite good watering. Turned out I had forgotten to fertilize for two months. Problem solved with regular feeding.

Problem: Long, Leggy Candles

Causes: Insufficient light or too much nitrogen

Solution: Move to a brighter location and reduce nitrogen fertilizer in spring.

Problem: Poor Back-Budding

Causes: Insufficient light to interior branches, too much vigor in upper canopy

Solution: Needle plucking helps tremendously. Also, control top growth more aggressively to redirect energy to lower branches.

Problem: Wire Scars

Causes: Leaving wire on too long—Scots Pine bark is softer than Japanese Pine

Solution: Check wire every 2-3 months. Remove before it bites. If scars occur, they’ll eventually heal, but it takes years.

I have permanent wire scars on one tree from leaving wire on over winter. Learn from my mistake.

Problem: Branch Die-Back

Causes: Insufficient light, overwatering, or damage to branch collar during pruning

Solution: Ensure all branches receive adequate light. Prune carefully. If a branch dies, remove it cleanly at the trunk.

Scots Pine Bonsai Care Sheet

| Aspect | Care Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Light | Full sun, minimum 6 hours daily. More is better. |

| Water | When soil surface is dry but moisture remains 1″ down. Daily in summer, weekly in winter. |

| Soil | Well-draining: 50% akadama, 30% pumice, 20% lava rock. |

| Fertilizer | Balanced organic fertilizer spring through summer. Low-nitrogen in fall. None in winter. |

| Temperature | Hardy to -15°C (5°F). Requires winter dormancy. |

| Repotting | Every 2-3 years (young trees), 3-5 years (mature). Early spring before bud break. |

| Pruning | Candle pruning in early summer. Needle plucking in fall. |

| Wiring | After new growth hardens (July-August). Use aluminum wire. Check frequently. |

| Pests | Generally pest-resistant. Occasional spider mites in hot, dry conditions. |

| Winter Care | Minimal watering. Can stay outdoors in most climates. Protect roots in extreme cold. |

Why I Recommend Scots Pine (With Caveats)

After seven years working with this species, here’s my honest assessment:

Scots Pine is ideal for:

- Bonsai enthusiasts in cold climates (zones 3-8)

- Practitioners wanting a hardy, forgiving pine species

- Anyone interested in European bonsai aesthetics

- Those who appreciate distinctive bark character

- People with outdoor growing space

Scots Pine is NOT ideal for:

- Indoor growing (requires dormancy)

- Hot, humid climates (zones 9-11)—though it can work with afternoon shade

- Practitioners wanting formal, symmetrical styles

- Impatient beginners wanting fast results

The bottom line: If you have outdoor space, live in a suitable climate, and want a pine bonsai that’s more forgiving than Japanese Black Pine but still offers plenty of challenge and character, Scots Pine is excellent.

My trees have taught me patience, shown me that European species deserve respect in the bonsai world, and given me some of my most satisfying styling experiences.

Would I recommend starting with Scots Pine as your first pine bonsai? Actually, yes. It’s tougher and more forgiving than people think. Just be prepared for a long-term relationship—these trees are at their best after 20-30 years of development.

Resources That Actually Helped Me

- Walter Pall’s blog (walter-pall.de) – German bonsai master who’s done incredible work with Scots Pine

- Bonsai Empire’s pine care guides – Good technical information

- European Bonsai San Show – Annual exhibition showcasing top European bonsai, including many Scots Pines

- “Pines” by Harry Tomlinson – Chapter on Scots Pine is excellent

- Local bonsai clubs in Scotland and Scandinavia often have specific expertise with this species

Final Thoughts

My first Japanese Black Pine died within a year. Too sensitive, too demanding, too unforgiving of mistakes.

My first Scots Pine is now seven years old, about 16 inches tall, styled in an informal upright, and steadily improving each year. It’s taught me more about pine bonsai than any book or video because it survived my mistakes and kept growing.

That’s the beauty of Scots Pine—it gives you room to learn, time to develop your skills, and eventually rewards your patience with a tree that captures the rugged beauty of European mountains.

If you’re considering your first pine bonsai, or if you’ve written off European species as inferior to Japanese material, give Scots Pine a chance. It might just change your perspective.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can Scots Pine bonsai be grown indoors?

A: No. Scots Pine requires winter dormancy and cannot survive indoors year-round. They need seasonal temperature changes and outdoor conditions to thrive.

Q: How long does it take to develop a Scots Pine bonsai?

A: From nursery stock, you can have a presentable bonsai in 5-7 years. A truly refined tree takes 15-25+ years. Collected material can look impressive much faster if the tree already has character.

Q: What’s the difference between Scots Pine and Japanese Black Pine for bonsai?

A: Scots Pine has shorter needles, orange-red bark, is more cold-hardy, and is generally more forgiving. Japanese Black Pine has darker bark, slightly longer needles, and is the traditional choice for formal pine bonsai. Both are excellent, just different.

Q: When should I prune candles on Scots Pine?

A: Wait until candles fully extend and needles just begin emerging—usually late May to early June in most climates. Timing varies by location, so watch your tree’s development.

Q: How often should I water my Scots Pine bonsai?

A: Water when the soil surface is dry but moisture remains about an inch down. In summer, this usually means daily watering. In winter, weekly or less. Adjust based on your climate and soil mix.

Q: Are Scots Pine bonsai suitable for beginners?

A: Yes, with caveats. They’re more forgiving than most pines, but still require outdoor space, proper dormancy, and basic understanding of pine care techniques. They’re excellent for adventurous beginners willing to learn.

Q: What size pot should I use for Scots Pine bonsai?

A: The pot should be approximately 2/3 the height of the tree for upright styles, or 2/3 the width for cascade styles. Depth should accommodate the root system with room for growth. Use unglazed, earth-toned pots for best aesthetics.

Q: Do Scots Pine bonsai produce cones?

A: Yes, mature trees will produce small cones. However, on bonsai, cones drain significant energy and are usually removed unless you specifically want them for aesthetic purposes or seed collection.

Q: What’s the best soil mix for Scots Pine bonsai?

A: A well-draining mix of 50% akadama, 30% pumice, and 20% lava rock works well. For younger trees, add 10-15% pine bark. The key is excellent drainage—Scots Pine tolerate dry conditions better than wet feet.

Q: How cold-hardy are Scots Pine bonsai?

A: Very hardy. They can tolerate temperatures down to -15°C (5°F) or lower without protection. In fact, they require winter dormancy and cold exposure to thrive.

Also Read: