Lodgepole Pine Bonsai: The Rocky Mountain Native Nobody Talks About

The Tree That Survived My Worst Bonsai Mistake

In 2016, I made a huge mistake. I took a Lodgepole Pine (Pinus contorta) from the Colorado Rockies at 9,000 feet, brought it home to Denver, and in July, right in the middle of the summer heat, planted it in a shallow bonsai pot. The timing could not have been worse. Every bonsai book says this is how you kill a pine. Every forum expert would have told me I was an idiot.

That tree is now eight years old, sitting on my bench, and it’s one of my healthiest pines. The trunk has incredible movement from years of fighting mountain winds. The bark is developing that rugged, weathered texture. And it’s taught me that Lodgepole Pine might be the most underrated and underutilized species in American bonsai.

This isn’t a tree you’ll find in Japanese bonsai books. There’s no centuries-old tradition of cultivating Pinus contorta. But after working with this species for nearly a decade, I’m convinced it deserves far more attention, especially from American bonsai practitioners looking for native material that actually thrives in our climate.

What is a Lodgepole Pine Bonsai?

Lodgepole Pine (Pinus contorta) is a two-needle pine native to western North America, ranging from the Yukon to Baja California and from the Pacific coast to the Rocky Mountains. In nature, these trees can grow straight and tall (hence “lodgepole” because Native Americans used them for tipi poles) or twisted and gnarled when growing in harsh alpine conditions.

For bonsai, we’re interested in the twisted, character-filled trees from high elevations and harsh environments. These naturally stunted specimens, shaped by wind, snow, poor soil, and extreme temperature swings, already look like bonsai before we even touch them.

A Lodgepole Pine bonsai is essentially a miniaturized version of those weathered alpine survivors. The needles are relatively short (1.5 to 3 inches), the bark develops interesting texture with age, and the species has a natural tendency toward irregular, characterful growth that translates beautifully to bonsai styling.

History and Cultural Context

Unlike Japanese Black Pine or even Scots Pine, Lodgepole Pine has no traditional bonsai pedigree. You won’t find it mentioned in classic bonsai texts or showcased in ancient collections.

But here’s the thing: American bonsai is finally coming into its own. We’re realizing we don’t need to slavishly copy Japanese traditions or import Japanese species to create compelling bonsai. We have incredible native material right here, and Lodgepole Pine is a perfect example.

The species has deep roots in Native American culture across the West. Various tribes used the straight-growing lowland trees for lodge poles, tool handles, and construction. The pitch was used for waterproofing and medicine. These trees have been part of the western landscape and human interaction with that landscape for thousands of years.

In modern bonsai, Lodgepole Pine started gaining recognition in the 1980s and 1990s as American collectors began working with native Rocky Mountain species. Artists like Ryan Neil (though he focuses more on other natives) helped legitimize American species, and Lodgepole benefited from that cultural shift.

I learned about Lodgepole’s potential from a local Colorado bonsai club member who had a collected tree that was absolutely stunning. All twisted trunk and dense foliage pads, looking like it had been fighting alpine storms for a century (which it probably had).

What Makes Lodgepole Pine Special for Bonsai

After eight years working with this species (three collected trees and two nursery-grown experiments), here’s what I’ve come to appreciate:

They’re Tougher Than You Think

Remember my terrible collection timing? That tree survived because Lodgepoles are remarkably resilient. In their native habitat, they endure temperature swings from negative 40°F to 90°F, intense UV radiation at high altitudes, poor rocky soil, months buried under snow, and hurricane-force winds.

That environmental toughness translates to bonsai cultivation. They tolerate mistakes better than many pine species. They bounce back from aggressive root work. They handle temperature extremes without complaining.

The Needles Are Actually Manageable

At 1.5 to 3 inches, Lodgepole needles are shorter than many pine species. With proper techniques (which I’ll detail later), you can get them down to 0.75 to 1.5 inches, perfectly proportional even on smaller bonsai.

The needles are a nice yellow-green to dark green, depending on growing conditions and genetics. They’re not as dramatically blue as some Scots Pines, but they have good color and density when the tree is healthy.

Natural Character From Harsh Environments

This is the big one. Trees collected from harsh alpine environments come pre-styled by nature. Trunks twisted from constant wind. Deadwood (jin and shari) created by lightning strikes and harsh weather. Compact growth from short growing seasons. Irregular branching that looks windswept and ancient.

My best Lodgepole came from a site at 10,200 feet where trees had maybe 60 frost-free days per year. The trunk spirals like a corkscrew, and half the tree is natural deadwood. I didn’t create that character, nature did. I’m just maintaining it.

They Actually Want to Be Small

Unlike some pines that fight you every step of the way to stay miniature, Lodgepoles from alpine environments are naturally compact. In harsh conditions, century-old trees might be only 6 to 8 feet tall with trunks 4 to 6 inches thick. That proportion (thick trunk, compact size) is exactly what we want in bonsai.

Back-Budding That Actually Works

Lodgepole Pines back-bud more readily than many pine species. Not as aggressively as Japanese Black Pine, but significantly better than many American natives. I’ve gotten adventitious buds on 5 to 7 year old branches by letting light into the interior through needle plucking and selective pruning.

Types of Lodgepole Pine

Pinus contorta has four recognized subspecies, and they’re quite different for bonsai purposes:

Shore Pine (Pinus contorta var. contorta)

This is the coastal form, found from Alaska to Northern California. It grows in sandy, poor soil near the ocean and develops incredibly twisted, gnarled forms even at sea level.

Characteristics: Extremely twisted trunks (even more than alpine forms), shorter needles, more tolerant of wet conditions, less cold-hardy.

Best for: Dramatic, twisted literati and driftwood styles

I haven’t personally worked with Shore Pine, but I’ve seen collected specimens that are absolutely spectacular. If you’re on the West Coast and can legally collect (big if, know your regulations), this form offers incredible natural character.

Rocky Mountain Lodgepole (Pinus contorta var. latifolia)

This is the interior/mountain form, the one I work with. It ranges through the Rockies from British Columbia to Colorado and New Mexico.

Characteristics: Variable growth habit depending on elevation. High-elevation trees are twisted, compact, and character-filled. Low-elevation trees are straighter and less interesting for bonsai. Very cold-hardy. Needles 1.5 to 3 inches.

Best for: All bonsai styles, especially collected alpine specimens

This is THE form for most American bonsai practitioners. If you’re in the Mountain West and interested in Lodgepole, this is what you’ll be working with.

Sierra Lodgepole (Pinus contorta var. murrayana)

Found in the Sierra Nevada and southern Cascades. Similar to the Rocky Mountain form but adapted to slightly different conditions.

Characteristics: Slightly longer needles than latifolia, can be very straight in good growing conditions, high-elevation trees develop good character, drought-tolerant.

Best for: Bonsai from harsh, high-elevation sites

Bolander’s Beach Pine (Pinus contorta var. bolanderi)

Rare coastal form from Northern California. Not commonly used in bonsai due to limited range and protected status in some areas.

For bonsai purposes, focus on Rocky Mountain form or Shore Pine depending on your location.

How to Grow a Lodgepole Pine Bonsai

Let me walk you through the practical reality of working with this species, what actually works versus what’s theoretical.

Getting Starting Material

You have three main options:

Option 1: Collected Material (My Recommendation, But Do It Right)

This is how you get the best Lodgepole bonsai. Period. Trees shaped by decades or centuries of harsh conditions have character you can’t create artificially.

Where to collect: High-elevation sites (8,000 plus feet in Colorado; varies by latitude), exposed ridges and rocky outcrops, areas with poor soil and harsh conditions. Look for naturally stunted trees with thick trunks and compact growth.

CRITICAL LEGAL NOTE: National Forests often allow personal collection with permits. National Parks: Collection is illegal, period. Private land: Get written permission. State and local regulations vary. Some areas prohibit collection entirely. Fines for illegal collection can be $5,000 plus and include criminal charges.

I collect with a valid Forest Service permit, only from designated areas, and I follow all regulations. Do the same or don’t collect at all.

Best collection timing: Early spring (March to April in Colorado) right before buds swell, or late fall (October to November) after growth stops. I’ve had success with both windows.

Collection process: Choose trees 1 to 3 inches trunk diameter (manageable size). Dig a wide root ball, minimum 12 inches diameter for a 2-inch trunk. Keep as many feeder roots as possible. Wrap root ball in burlap or plastic. Get it home and planted within hours. Place in pure pumice or coarse substrate for first year. Don’t style or prune for 1 to 2 years, let it recover.

My collected trees spent their first year in wooden grow boxes filled with 100% pumice. Boring, but they all survived and thrived.

Option 2: Nursery Stock (Limited Availability)

Finding Lodgepole Pine in regular nurseries is tough. They’re not popular landscape trees outside their native range. But if you’re in the Mountain West, some native plant nurseries carry them.

What to look for: Avoid perfectly straight, telephone-pole trunks. Look for any trunk movement or taper. Check for low branches (first branch within lower third of trunk). Smaller is often better, easier to develop taper and movement.

I found one at a native plant sale in Denver three years ago. It’s developing nicely but will never have the character of collected material.

Option 3: Seeds (For the Very Patient)

Growing from seed means 15 to 20 years before you have anything resembling a bonsai. But if you’re young, patient, or want maximum control over development, it’s an option.

Seeds need cold stratification (60 to 90 days at 34 to 40°F) before germination. Plant in spring. Grow in the ground or large containers for 5 to 7 years to develop trunk thickness.

I started some seedlings as an experiment. They’re five years old and pencil-thick. I’ll check back in 2035.

Soil Mix That Works

Lodgepole Pines grow naturally in poor, rocky, well-draining soil. Replicate that in your bonsai pot.

My mix for established trees: 60% pumice, 30% lava rock, 10% pine bark

For collected trees (first 1 to 2 years): 90% pumice or coarse perlite, 10% pine bark

The key is drainage. These trees grow in rocky mountain soil where water drains instantly. Heavy, organic soil will kill them through root rot faster than almost anything else.

I learned this when a tree in 40% organic soil developed root rot. Now I’m religious about drainage.

Location and Climate Requirements

Lodgepole Pines need full sun (minimum 6 hours, but 8 plus is ideal), cold winters (they require dormancy; trying to grow them in warm climates like zones 9 to 11 is a losing battle), good air circulation (prevents fungal issues and mimics their native windy habitat), and protection from extreme heat (they’re mountain trees; 100°F plus weather stresses them).

My trees stay outside year-round in Denver (zone 5b). Winter temperatures regularly hit 0 to 10°F, sometimes lower. The trees don’t care, they’re built for it.

In summer, I provide afternoon shade during heat waves above 95°F. They can handle it, but they’re not thriving in that heat. They want 60 to 85°F summers, not 95 to 105°F.

Watering Strategy

This is where Lodgepole differs from many pines. They’re slightly more tolerant of moisture than species from drier climates.

My approach: Water when soil surface is dry but slight moisture remains 1 inch down. In summer, daily, sometimes twice on very hot days. Spring and fall, every 2 to 3 days. Winter, weekly, or when soil thaws if frozen.

They tolerate brief dry periods better than staying constantly wet. If I had to choose between slightly too dry or slightly too wet, I’d choose dry every time.

Signs of watering problems: Too dry means needles turn yellow-brown at tips and growth slows. Too wet means needles yellow from base, mushy roots, and fungal smell from soil.

Fertilizing Schedule

Lodgepoles aren’t heavy feeders in nature. They grow in nutrient-poor soil. But bonsai in small pots need supplemental nutrition.

My fertilizing program: Spring (March to May), balanced organic fertilizer (5-5-5 or similar) applied every 3 to 4 weeks. Summer (June to August), continue balanced fertilizer. Late Summer (August to September), switch to low-nitrogen (0-10-10) to harden growth. Fall and Winter (October to February), no fertilizer during dormancy.

I use organic pellets (Biogold or similar) because they release slowly and I can’t burn the tree. I’ve also used diluted liquid fertilizer (fish emulsion, Neptune’s Harvest) with good results.

Mistake I made: Over-fertilizing a young tree caused excessive, leggy growth that looked terrible. Less is more with Lodgepole.

Pruning and Needle Management

Here’s where Lodgepole is both easier and more challenging than Japanese pines.

Candle Pruning: Lodgepoles produce spring candles like other pines. To control needle length and promote back-budding, wait until candles fully extend but before needles fully open (usually late May to early June in Denver). Strong candles: Cut back 50 to 70%. Weak candles: Cut back 30 to 50% or leave alone. Very weak areas: Don’t prune at all.

The timing window is shorter than Japanese Black Pine, maybe 7 to 10 days when candles are at the perfect stage. Miss it and you’re waiting until next year.

Needle Plucking: Critical for maintaining interior growth and managing vigor.

Fall needle plucking (September to October): Keep current year’s needles. Remove 50 to 80% of previous year’s needles. Remove all needles older than 2 years. Focus on plucking from strong areas to redirect energy to weaker zones.

My first attempt at needle plucking was way too conservative. I removed maybe 20% of old needles and saw minimal benefit. Now I’m more aggressive, and the trees respond with better back-budding and more compact growth.

The Rule: If light isn’t reaching interior branches, you won’t get back-budding. Be aggressive with needle plucking.

Wiring and Styling Techniques

Lodgepole branches are moderately flexible when young but become brittle with age, standard for pines.

Wiring guidelines: Best timing is after new growth hardens in summer (July to August). Wire type is aluminum for most work; copper for heavier branches on mature trees. Duration: Check every 2 to 3 months; remove before wire bites (faster than you think). Technique: Wire from bottom to top, working with the natural movement.

Styling considerations: Lodgepole’s natural growth suggests certain styles.

Best styles: Literati (Bunjin) is perfect for naturally twisted alpine specimens. Informal Upright works with the irregular growth pattern. Windswept matches their natural habitat appearance. Slanting shows natural lean from mountainside growth.

Styles that don’t work: Formal Upright looks forced and unnatural. Broom is not suited to pine architecture.

My best tree is styled as a twisted literati with extensive natural deadwood. I didn’t impose a style, I just enhanced what nature already created.

Repotting Requirements

Lodgepole Pines develop strong root systems that can become pot-bound within 2 to 3 years when young.

Repotting schedule: Young trees (under 10 years), every 2 to 3 years. Mature trees (10 to 25 years), every 3 to 4 years. Old collected specimens, every 4 to 5 years.

Best timing: Early spring (March to April in my climate) just before buds swell. I can see the buds starting to enlarge but they haven’t opened yet. That’s the perfect window.

Repotting process: Remove tree from pot. Rake out old soil from outer 30 to 40% of root ball. Trim circling roots and prune 20 to 30% of root mass. Position in new or same pot with fresh soil. Water thoroughly. Protect from wind for 2 to 3 weeks while roots establish.

Mistakes I’ve made: Repotting too late (after buds opened), tree sulked all summer. Removing too much root mass (50% plus), tree barely grew for two years. Using pot that was too large, growth was vigorous but diffuse, not compact.

Benefits of Growing Lodgepole Pine Bonsai

After eight years with this species, here’s what I genuinely value:

Native American Species

If you’re in the western U.S., working with Lodgepole Pine connects you to your local landscape. You’re not trying to recreate Japanese mountainsides in Colorado. You’re miniaturizing the actual mountains you can see from your backyard.

There’s something satisfying about that authenticity. These trees evolved here, thrive here, and represent this landscape.

Exceptional Cold Hardiness

Zone 3 to 8 growers, rejoice. Lodgepole handles serious cold without protection. I’ve had trees survive negative 15°F with no damage. Try that with Japanese Black Pine or Chinese Elm.

This cold hardiness also means reliable dormancy. No need to provide artificial chilling or worry about warm winters disrupting the trees’ cycle.

Collected Material with Instant Character

A 50-year-old collected Lodgepole can look like a finished bonsai with minimal work. The trunk movement, deadwood, and compact growth are already there. You’re just refining and maintaining what nature created.

Compare that to nursery stock, which typically needs 10 to 15 years of development before it looks like a real bonsai.

They’re Surprisingly Forgiving

Despite being pines (generally considered advanced species), Lodgepoles tolerate mistakes better than their reputation suggests. They bounce back from overly aggressive root pruning, poorly timed repotting, drought stress, cold damage, and training errors.

This doesn’t mean you should be careless, but they give you room to learn.

Unique Aesthetic

Nobody else at the bonsai club has Lodgepole Pine. You’ll have Japanese Black Pine, Chinese Elm, and Juniper coming out of your ears, but Lodgepole? That’s unusual. That’s interesting. That starts conversations.

Lower Cost Entry

Collected trees are free (if done legally with permits). Even purchasing from collectors who specialize in native material costs significantly less than imported Japanese material or attending workshops with famous artists.

My total investment in my best Lodgepole: $30 for the collection permit, $15 for gas to drive to the collection site, and $0 for the tree itself.

Styling and Design Philosophy

The best Lodgepole bonsai I’ve seen share certain characteristics:

Work With Natural Character, Not Against It

Collected Lodgepoles come with built-in movement, deadwood, and growth patterns shaped by their environment. Your job isn’t to impose a predetermined design. It’s to enhance what’s already there.

My first collected tree had a natural rightward lean. I initially tried to wire it more upright because I thought “upright is more formal and refined.” It looked terrible, forced and unnatural.

I rewired it following the natural lean, emphasized the windswept character, and suddenly it looked right. Lesson learned.

Embrace Deadwood

Alpine Lodgepoles often have significant natural deadwood from lightning strikes, broken branches, and harsh weather. That deadwood is a feature, not a flaw.

Preserve it. Clean it. Maybe carve it slightly to enhance the weathered appearance. But don’t remove it to create a “perfect” green tree. The deadwood tells the story of the tree’s life in the mountains.

Keep It Rugged

Lodgepole isn’t a refined, manicured species. It’s not Japanese Black Pine with perfect, symmetrical branch pads. It’s rough, irregular, windswept, and weathered.

Trying to create perfectly balanced, symmetrical designs looks wrong on Lodgepole. Embrace asymmetry. Allow some branches to be thicker or longer than classical proportions suggest. Let the tree look like it’s been fighting mountain storms because in many cases, it has.

Consider the Natural Environment

In their native habitat, Lodgepoles grow on exposed ridges (windswept styles work perfectly), in rocky soil (exposed root-over-rock designs are natural), at high elevations (compact, dense foliage with short needles), and among granite boulders (consider companion stones in the pot).

Your bonsai should evoke that mountain landscape. When I display my Lodgepoles, I use companion accent plants native to the same ecosystem: alpine wildflowers, small sedges, or native grasses. The entire presentation tells a story about the Rocky Mountain environment.

Pot Selection

Lodgepole Pines look best in unglazed pots with earthy browns, grays, and tans. Rough textures work best. Smooth, refined pots clash with the rugged character. Natural colors are ideal; avoid bright glazes. Masculine, angular shapes are generally better than round, feminine forms.

I made the mistake of putting a tree in a smooth, refined, gray-green glazed pot. It looked too refined, too polished for the rugged tree. Now it sits in an unglazed, rough-textured brown pot that matches the bark tones. Much better.

Seasonal Care Guide

Spring (March to May)

Spring is busy season. The trees wake up, buds swell, and candles emerge.

Tasks: Repot if scheduled (before buds open). Begin fertilizing when buds swell. Monitor candle development. Plan your candling strategy. Remove winter protection (if any). Check wire from previous year.

What to expect: New candles emerge in late April or early May (in Denver). They’ll extend rapidly, sometimes 3 to 4 inches in two weeks.

Summer (June to August)

This is candling season and the main growing period.

Tasks: Execute candle pruning (early to mid June). Continue regular watering (often daily). Maintain fertilization schedule. Wire new growth after it hardens (July to August). Watch for pests (rare but possible).

What to expect: After candling, trees will push a second flush of growth with shorter needles. This is exactly what you want.

Fall (September to November)

Needle plucking season and preparation for dormancy.

Tasks: Needle plucking (September to October). Switch to low-nitrogen fertilizer. Remove biting wire. Final styling or wiring before dormancy. Prepare for winter.

What to expect: Growth slows significantly. Needles may yellow slightly before dormancy. This is normal.

Winter (December to February)

Trees are dormant. Not much to do except basic maintenance.

Tasks: Minimal watering (weekly or less). Protect from extreme temperature swings (though Lodgepole is very hardy). Check for winter damage after storms. Plan next year’s development.

What to expect: Trees will look dormant with no active growth and slightly dull needle color. This is completely normal and necessary.

Common Problems and Solutions

Yellow Needles (Non-Seasonal)

Causes: Overwatering, underwatering, nutrient deficiency, or root problems

Solution: Check soil moisture. Is it soggy or bone dry? If overwatering, reduce watering, check drainage, possibly repot. If underwatering, increase consistency. If neither, check fertilization schedule.

I had yellowing on one tree that turned out to be iron deficiency (chlorosis). Solution: Chelated iron supplement and slight lowering of soil pH.

Weak Back-Budding

Causes: Insufficient light reaching interior branches, too much vigor in apex

Solution: Aggressive needle plucking in fall. Control apex vigor through selective pruning. Ensure adequate fertilization (but not excess). Be patient. Lodgepole back-buds, but not instantly.

Die-Back of Lower Branches

Causes: Insufficient light, apex too vigorous, or branch too weak

Solution: Increase light to interior. Control apex through pruning and needle removal. Don’t let strong upper branches shade out lower ones. If branch is dying, remove it cleanly rather than leaving a dying stub.

Excessive Needle Length

Causes: Too much nitrogen, insufficient light, or missed candling timing

Solution: Reduce nitrogen fertilizer. Ensure full sun exposure. Time candle pruning correctly next year. Use more aggressive needle plucking.

Wire Scars

Causes: Leaving wire on too long (Lodgepole grows quickly in favorable conditions)

Solution: Check wire every 2 to 3 months during growing season. Remove before it bites. If scars occur, they’ll eventually heal, but it takes 3 to 5 plus years.

I have permanent wire scars on my first collected tree from leaving wire on over one growing season. Learn from my expensive mistake.

Slow Growth After Collection

Causes: Root damage during collection, collection timing, or insufficient root mass

Solution: Be patient. Collected trees can take 2 to 3 years to fully recover. Keep in coarse substrate for first 1 to 2 years. Don’t style or prune heavily until vigorous growth returns. Protect from extreme conditions while recovering.

Lodgepole Pine Bonsai Care Sheet

| Aspect | Care Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Light | Full sun, minimum 6 hours daily. 8 plus hours ideal. Afternoon shade in extreme heat. |

| Water | When soil surface dry but moisture remains 1 inch down. Daily in summer, weekly in winter. |

| Soil | Well-draining: 60% pumice, 30% lava rock, 10% pine bark. Drainage is critical. |

| Fertilizer | Balanced organic fertilizer spring through summer. Low-nitrogen in fall. None in winter. |

| Temperature | Hardy to negative 40°F. Requires winter dormancy. Best in zones 3 to 8. |

| Humidity | Tolerates low humidity. Native to relatively dry mountain climates. |

| Repotting | Every 2 to 3 years (young trees), 3 to 5 years (mature). Early spring before bud break. |

| Pruning | Candle pruning in early summer when candles extend. Needle plucking in fall. |

| Wiring | After new growth hardens (July to August). Use aluminum. Check frequently for wire bite. |

| Pests | Generally pest-resistant. Occasional aphids or spider mites in stress conditions. |

| Winter Care | Very cold-hardy. Can stay outdoors year-round in zones 3 to 8 without protection. |

Who Should (and Shouldn’t) Grow Lodgepole Pine

After eight years with this species, here’s my honest assessment:

Lodgepole Pine is Ideal For:

Bonsai practitioners in the western U.S. (especially Rocky Mountain region). Cold-climate growers who struggle with tender species. Collectors with access to legal collection sites. People interested in native American bonsai material. Pine enthusiasts wanting something different from Japanese species. Intermediate-level practitioners ready for pine bonsai.

Lodgepole Pine is NOT Ideal For:

Warm climate growers (zones 9 to 11), they need cold winters. Indoor bonsai enthusiasts, these must be grown outdoors. Absolute beginners, start with easier species first. People without outdoor space, they need full sun and weather exposure. Practitioners wanting formal, refined styles, Lodgepole is naturally rugged. Those far from the western U.S., nursery availability is limited.

The Bottom Line

Lodgepole Pine is a fantastic species if you live in zones 3 to 8, ideally in the Mountain West. You have outdoor growing space with full sun. You appreciate rugged, naturalistic aesthetics over refined formality. You can legally access collection sites or find nursery-grown material.

If you meet those criteria, Lodgepole might become one of your favorite species, like it has for me.

If you’re in Florida or Southern California wanting to grow Lodgepole indoors, I’ll save you the frustration: Don’t. Choose a species suited to your climate instead.

Resources and Further Learning

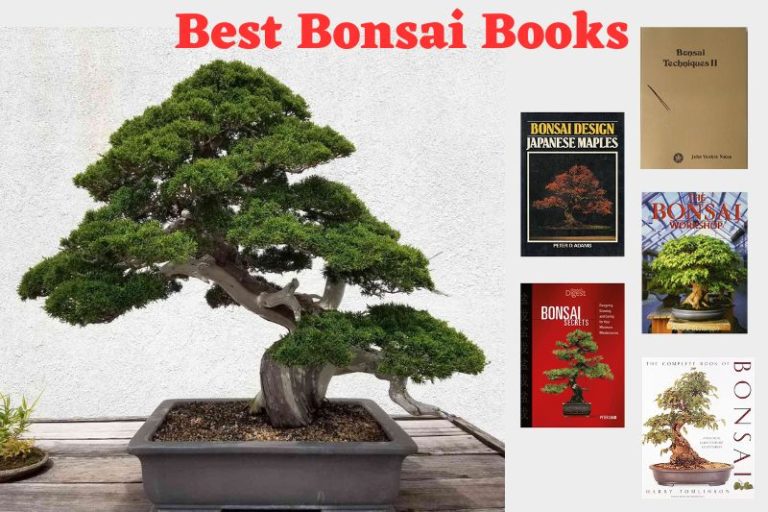

Books and Publications: “Native Plants for High-Elevation Western Gardens” by Janice Busco and Nancy R. Morin includes Lodgepole ecology. “Bonsai Today” Issues from the 1990s to 2000s have occasional articles on American natives. “Rocky Mountain Alpines” by Kelly Grummons gives context on high-elevation plant communities.

Online Resources: Rocky Mountain Bonsai Society (if you’re in Colorado) has local expertise on mountain natives. Bonsai Nut forums, search “Pinus contorta” for collection and care threads. IBC (Internet Bonsai Club) has good archive of American pine work.

Practitioners to Follow: Ryan Neil (Bonsai Mirai), while he focuses on other natives, his principles apply to Lodgepole. Walter Pall, European perspective but works with similar two-needle pines. Local collectors in your region, find them through regional bonsai clubs.

Where to See Examples: National Bonsai Exhibition (Rochester, NY) has occasional American natives. Pacific Bonsai Museum (Seattle) has some native American material. Regional Rocky Mountain exhibitions are the best place to see Lodgepole specifically.

Final Thoughts: Why This Species Matters

I’ve worked with Japanese Black Pine, Scots Pine, Japanese White Pine, and several other pine species. Each has merit. Each is beautiful in its own way.

But Lodgepole Pine represents something different: American bonsai coming into its own.

We don’t need to exclusively work with imported Japanese species or copy Japanese aesthetics to create compelling bonsai. We have incredible native material that’s perfectly adapted to our climate, reflects our landscapes, and tells our stories.

My collected Lodgepole, the one I nearly killed with terrible collection timing, sits on my bench next to a Japanese Black Pine I’ve been working on for six years. The Japanese tree is technically superior, more refined, more “correct” by classical standards.

But the Lodgepole? That tree captures the Rocky Mountains I can see from my backyard. It reminds me of hiking at timberline. It represents decades of wind and weather shaping a tree into something resilient and characterful.

That connection to place, that authenticity, you can’t import it or copy it from a book. You have to work with your local material and let it teach you what it wants to be.

If you’re in the western U.S. and haven’t tried Lodgepole Pine, give it a shot. Visit the mountains. Look for naturally stunted trees with character. Get a legal collection permit. Bring one home carefully and respectfully.

It might just change how you think about bonsai.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Where can I buy Lodgepole Pine for bonsai?

A: Lodgepole isn’t commonly available at regular nurseries outside its native range. Try native plant nurseries in the Mountain West, bonsai clubs with member sales, online bonsai retailers specializing in American natives, or collect your own with proper permits.

Q: Can I grow Lodgepole Pine bonsai indoors?

A: No. Lodgepole Pine requires winter dormancy and outdoor conditions. They cannot survive long-term indoors. They need seasonal temperature changes, full sun, and natural weather exposure to thrive.

Q: How long does it take to develop a Lodgepole Pine bonsai?

A: From nursery stock, expect 7 to 10 years for a presentable bonsai. A refined tree takes 15 to 25 plus years. Collected material from harsh environments can look impressive immediately with minimal styling, though it still needs years of refinement.

Q: What’s the difference between Lodgepole Pine and Japanese Black Pine for bonsai?

A: Lodgepole has shorter needles, lighter colored bark, is more cold-hardy, and is more forgiving of mistakes. Japanese Black Pine has darker bark, slightly different needle characteristics, and centuries of bonsai tradition behind it. Both are excellent, just different.

Q: When should I prune candles on Lodgepole Pine?

A: Prune candles when they fully extend but before needles fully open, usually late May to early June in most climates. The timing window is short (7 to 10 days), so watch your tree carefully. Timing varies by location and weather.

Q: How often should I water my Lodgepole Pine bonsai?

A: Water when the soil surface is dry but moisture remains about 1 inch down. In summer, this usually means daily watering, sometimes twice on very hot days. In winter, weekly or less. Adjust based on your climate and soil mix

Also Read: